A few decades back, Edward deBono labeled this kind of breakthrough thought with the phrases "out of the box" and "lateral thinking." He claimed that vertical thinking - logical and analytical - is the norm in most teams while there is little skill or attention devoted to exploration.

1. Wondering

Wondering helps an organization combat lethargy, complacency and stasis. In all too many cases, the norm is "Leave well enough alone." A business or agency can lapse into a steady state doing business as usual while falling short of performance goals and gradually losing touch with changing conditions and expectations.

Wondering is a style of exploration that takes us outside of our comfort zones into unfamiliar territories.

- • I wonder what could go wrong.

• I wonder what our customers are thinking of us and whether they are still happy.

• I wonder which external conditions are changing most dramatically or consequentially.

• I wonder what we should be wondering or worrying about?

• I wonder how we could make wondering a prized organizational activity.

Those who prefer the monkeys' mode of planning (see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil) will wonder how wonder might prove useful. They will be so deep within the grasp of denial and self-delusion, they will have lost their sense of wonder and replaced it with certainty, conviction and blind faith.

Wondering can be characterized (uncharitably) as a fringe activity by those who prefer schematics and logical analytical approaches, but wondering is fundamentally centrist and quite conservative - a form of centering akin to the potter's centering of a lump of clay on the wheel.

The organization that fails to wonder is in danger of being marginalized (moved to the fringe) by changing conditions that it did not notice in time to respond. Ironically, closed mindedness leads to isolation from reality and premature obsolescence. Sometimes success becomes its own worst enemy as a team clings to the familiar and stops noticing what works and what fails. The tried and true becomes a blinder blocking out essential data.

2. Exploring the Edges

- "The larger the island of knowledge, the longer the

shoreline of wonder."

-- Ralph W. Sockman

Melville warned in Moby Dick of those who clung by habit to the lee shore:

- But as in landlessness alone resides the highest truth,

shoreless, indefinite as God --so, better is it to perish

in that howling infinite, than be ingloriously dashed

upon the lee, even if that were safety!

Organizations that hope to adjust to changing conditions in a healthy and timely manner invest in various forms of wondering that may range from somewhat formal models of scenario-building and focus groups to scouting, excursions and less formal modes of exploration.

To avoid marginalization and extinction or failure, such organizations expect many members of the leadership team to devote considerable attention to the margin, itself.

Related words help to define the focus:

- side, verge, border, perimeter, brink, brim, rim, fringe,

boundary, limits, periphery, bound, extremity

Instead of staying inside the fence and inside the yard, the organization explores the edges and what may lie in the negative spaces beyond. The team learns to leave the comfort zone on frequent expeditions.

Shawn Colvin captures this wondering on a personal basis in her song, "Summer Dress," the lyrics for which can be found at http://www.metrolyrics.com/lyrics/2147434523/Shawn_Colvin/Summer_Dress

- I went out to face the wilderness.

- We never lived. We just survived."

Colvin's 2006 collection, These Four Walls, offers quite a few songs exploring the theme of walls, limits, boundaries and the power of wondering.

Often, the wilderness offers the key to a brilliant future.

3. The Comfort Zone

All too often, we may dwell in the comfort zone, clinging, as Melville would put it, to the lee shore.

We are all, to some extent, creatures of habit. We rely upon and trust routines to guide many of our actions and decisions. We often seek manuals or guides to "show us the way." Much like deer returning to a favorite water hole, we have our cherished pathways and traditions. These habits, routines, guides, pathways and traditions combine with beliefs to create a culture, a way of living which serves the very desirable purpose of pulling us together.

Much of our adult life is devoted to the development of reliable routines and habits which will operate smoothly and predictably to produce the outcomes we seek. We seek to figure out the system. We are careful about rocking the boat lest we spill wind from the sails and lose headway. We become expert.

We (think) we know what we are doing. We (think) we know we will do it well.

The rules are clear. The expectations can remain unspoken. We can rely upon what has worked in the past. The secrets of success are public knowledge.

We need no high priestess or medicine men. We need no magic or sacrifice. We can ignore omens and signs. The future has been decided. We have its picture in hand.

No need or room for wonder in such organizations.

In times of rapid change and turbulence, what worked yesterday may not work today. In such times, the comfort zone is much like the sand into which the ostrich sticks its head - or the wall on the cover of this book.

Unfortunately, life in the comfort zone is addictive for many. Once we have tasted the security and predictability of life in the comfort zone, our desire for comfort often seems to grow and we require ever larger doses to maintain equilibrium. We begin to confuse the comfort zone and the feelings it generates with normality - the "way it's spozed to be."

Comfort is normal, we feel. Discomfort is abnormal. Risk is an enemy because it threatens disruption. Adventure is a high stakes gamble. Leadership (unfortunately) becomes the ability to provide and maintain comfort, raising high the walls that keep outside pressures from penetrating and upsetting the normal way. It is not the kind of influence once provided by whaling captains or wagon masters.

Real leadership seeks a balance between the very real benefits of stability on the one hand and adventuring and wondering on the other hand. Too much stress on either end of the scale can be dangerous.

A degree of stability is essential for performance to be strong. If the rate and level of change is too high and amounts to disruption, key players will lose their balance so that performance suffers. People within the organization need some degree of predictability and certainty. If rules and procedures are generally unclear and shifting, anxiety will undermine effectiveness.

At the same time, organizations may invest too heavily in stability, thereby ignoring messages from outside the organization that suggest the need for changes. If the organization fails to heed these messages, it may not move swiftly enough to adjust its operations.

At a minimum, an organization should devote resources to interpreting outside pressures and developments. Instead of ignoring such developments, the organization sends key staff to the crow's nest to scan the horizon and keep a lookout for new threats and possibilities. Some people are charged with thinking the unthinkable and wondering about the future.

This process will require more than a passing acquaintance with negative space.

4. Exploring Negative Space

Artists frequently employ the concept of negative space to capture the shape of spaces surrounding an object.

The same concept works well to identify the missing parts of a mental puzzle or an organizational challenge.

We try to extend our search beyond the boundaries of what we already know. We aim our searchlight into the shadows and the dark places.

We cast light into corners, under bushes, into closets, and through locked doors and barriers.

Wondering combines with wandering to help us turn our attention where it needs to rest.

- • What strategies allow us to penetrate the fog, sailing through darkness to emerge with increased understanding?

• How do we achieve illumination?

• How do we shed preconceptions, bias and false certainties?

• How can we create a map of regions never explored?

• Can we figure out what it is we do not know?

This chapter suggests three strategies, but there are many others worth adding to an organization's repertoire or skill set. These three are listed as examples to spur the team toward the finding and learning of others. More will be mentioned in Chapter Six - "The Apparently Irrelevant Question."

5. Strategy One - Ask the Court Jester or Clown

Ancient kingdoms employed court jesters or fools to help the ruler avoid folly. This job role is sadly lacking in most organizations today in any formal sense, although fools may be in ample supply. The jester is actual an important source of insight, using humor to challenge the direction and planning of the team or leader. Because many organizations are slow to question the leader's or their own visions, formalizing this function is a way of insuring against blind loyalty and the dangers that accompany leader worship.

The jester may be an internal staff consultant or someone hired to come in periodically from the outside whose task it is to help the team see folly it may have embraced without realizing it.

6. Strategy Two - Purposeful Wandering - Learning to Get Lost!

- “Not until we are lost do we begin to understand ourselves.”

Henry David Thoreau

The leadership team learns to leave what is known and familiar in order to taste the unfamiliar and bring fresh concepts and perspectives to its work. The wandering is purposeful and strategic, welcoming surprise and intent on discovering new insights and possibilities to enrich the planning and performance of the group.

Members of the team take excursions, some of which involve travel to unusual places, provocative conferences and environments likely to stimulate new thoughts. Excursions may also take less physical form as in reading or researching in unusual places, seeking novel sources and unlikely inspiration.

In seeking new possibilities, the leader becomes what the French would call a flâneur - someone who wanders about, strolling, exploring and discovering. It is noteworthy that the word "possibilities" captures both opportunity and risk, as the Apple dictionary/thesaurus reports the following related words:

- risk, hazard, danger, fear

option, alternative, choice, course of action, solution

potential, promise, prospects

The original flâneur in the days of Baudelaire was a bit of a dilettante and probably not especially purposeful, but the term has taken on some different meanings in recent times. One planning firm Urban Paradoxes® defines the process as follows:

- "Walking the city" – the act of the flâneur or wandersmänner – discovers the hidden stories by playfully combining all the senses, including the imagination, with technical analysis to discover both neighborhood narratives – of people, buildings, landscape, and infrastructure – and the core behaviors embedded in them.

The team becomes highly skilled at exploration and discovery - finding, locating, uncovering and unearthing the ingredients of a new policy, a new strategy, a new product or a new twist of some kind by wandering into new terrain.

In order to focus on terrain that might not naturally come to mind, the group learns to stumble upon the novel and the unusual. They learn to chance on, happen on, bump into, and light on information, ideas and experiences that are inspirational. Much of this unfamiliar material may seem revolutionary and startling at first so the team must come to grips with the unconventional and the exotic.

It is a challenge for most groups to elevate "stumbling" to an esteemed position in the organizational skill set, but the conscious effort to bump into material that will prove catalytic is an essential process for all groups hoping to make smart moves in a complicated environment.

7. Strategy Three - On the Outside Looking In

Most teams plan from within the organization, captured to some extent by the internal culture along with its traditions, beliefs and ways of doing things. These internal perspectives are important but limiting. Those who are close to the operation may have difficulty critiquing, understanding and improving how things are done when they are fully immersed in operations.

The leadership team may hire outside thinkers to help them view the operations from the outside or members may be appointed to step outside of the operations briefly to simulate the process of evaluating procedures from the outside.

The internal group conducting such a review or critique will operate much like a team of anthropologists visiting a culture. The key to their success is probing questions.

- • Who are these people?

• What are they trying to do?

• How are decisions being made?

• What are the main rituals?

• What are the belief systems?

• What is going wrong?

• What are the group's main failings?

• What are the group's main blind spots?

• What do they need to change?

But like real outsiders, this team may have difficulty sharing its findings in ways that will catch the attention of the other insiders. The critique and its recommendations may fall on deaf ears much as the report of the Iraq Study Commission was pretty much ignored at the end of 2006 by an administration clinging to its misconceptions and failed policies.

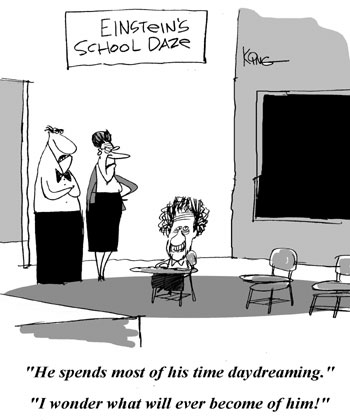

Each chapter of Leading Questions will include one or more cartoons as well as quotations from famous people.

Each chapter of Leading Questions will include one or more cartoons as well as quotations from famous people.