Please feel free to e-mail this article to a friend, a principal, a parent, a colleague, a teacher librarian, a college professor, a poet, a magician, a vendor, an artist, a juggler, a student, a news reporter or anyone you think might enjoy it. Other transmissions and duplications not permitted. (See copyright statement below).

Embracing Complexity

By Jamie McKenzie

About Author

We live in times awash in simplicity and simple-minded thinking.

But life is not simple. Nor are the challenges and issues facing us all, yet our culture seems to thirst for simple answers to complex problems.

Schools must engage students in research and learning requiring them to construct answers and make up their own minds. They must teach the young to embrace complexity while finding their way toward understanding.

|

|

|

Learners use skills, resources and tools to:

- Inquire, think critically, and gain knowledge.

- Draw conclusions, make informed decisions, apply knowledge to new situations, and create new knowledge.

- Share knowledge and participate ethically and productively as members of our democratic society.

- Pursue personal and aesthetic growth.

|

| A thirst for simple answers to complex problems?

Sadly, we see a drift toward mentalsoftness and a preference for entertainment over hard news.

Pandering to these wishes are a host of politicians, pundits, talk show hosts, commentators and modern day self-appointed soothsayers quick to offer up nonsense - simple minded solutions to complicated problems.

Problems with illegal immigrants? Build a wall.

Problems with schools? Test students much more frequently.

Problems balancing the budget? Borrow, print money and give tax cuts.

Sadly, decades of school research rituals reinforce a cut and paste mentality that leaves citizens poorly equipped to think for themselves or manage complexity. Topical research requires little more than scooping and smushing.

Schools must end these rituals and engage students in research that requires that they construct answers and make up their own minds. They must teach the young to embrace complexity.

The AASL Standards for the 21st-Century Learner posted at the outset of this article provide a clear direction for this effort.

|

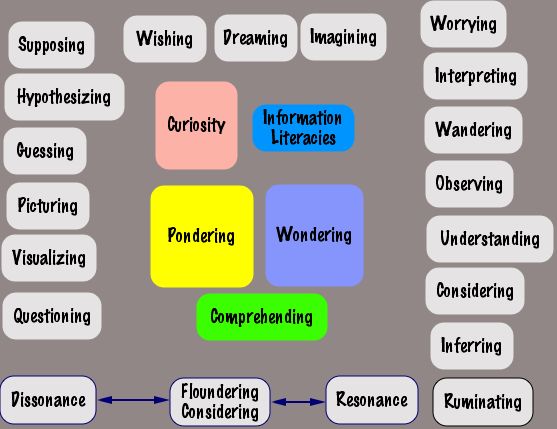

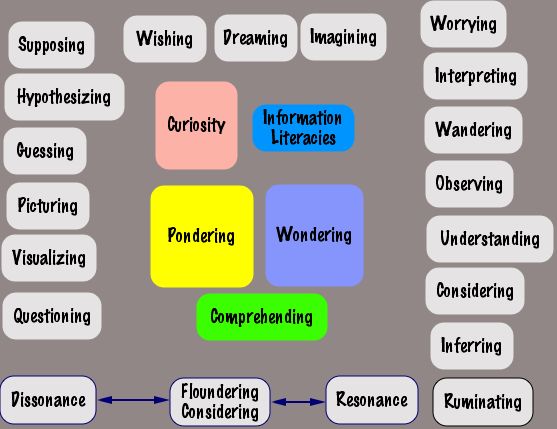

Following the publication of Learning to Question to Wonder to Learn, I began asking audiences to ponder a diagram much like the one below. Comprehending shares center stage with curiosity, pondering, wondering and a dozen information literacies.

Most times I have asked what they found most surprising about the collection of words, and their responses have varied considerably. Worrying and wandering draw many votes along with floundering.

During this time, I came to appreciate the value of "growing" a diagram like this one, adding new words and concepts as they came to mind. Frequently I added a word because it seemed delightful or illuminating, but at other times I found myself adding ideas that seemed tangential or even discordant. The diagram began to stretch out of shape in surprising ways, and this stretching was productive rather than disturbing.

Instead of compressing or simplifying the array as a cook might reduce a sauce, I came to see that extension and elaboration were valuable. Value resulted from juxtaposition and dissonance. The odd mixture was provocative and productive.

I first tasted this approach playing with clusters of words on the Visual Thesaurus. Give it a try.

Search for "question" on the Visual Thesaurus and surprising words appear like "marriage proposal" (as in "pop the question.") The same happens with many other words. Our understanding is expanded rather than compressed.

This cartoon is from Leading Questions

by Jamie McKenzie © 2007

|

| Later in this article, we will explore how schools can encourage students to embrace complexity and manage ambiguity while developing advanced comprehension skills that will help them pierce through the fog of modern and post modern life.

We will consider the relationship between comprehending on the one hand and curiosity, pondering, wondering and a dozen information literacies on the other hand.

|

A foggy day in Shanghai. © 2008, Jamie McKenzie

|

Pandering to Simple-Mindedness as an Industry

We are offered dozens of books devoted to Dummies . . .

- Taxes for Dummies

- Leadership for Dummies

- The Bible for Dummies

- Voting for Dummies

- Parenting for Dummies

This cultural drift is ominous. If we have so little tolerance for what Michael Leunig calls "the difficult truth," (see his poem Verity) then how can we hope to wrestle with reality?

As Beth Orton sings . . .

"Reality never lives up to all that it used to be."

Later she adds, "The best part of life, it seemed, was a dream."

Lyrics from "Best Bit" on her album Pass in Time (2003)

As Stephen Colbert has suggested, perhaps the very nature of reality is up for grabs these days as various groups pay to shift Wikipedia entries to cast a kinder light on their activities and products - Wikilobbying, as he calls it:

- "When money determines Wikipedia entries, reality becomes a commodity."

"IBM could throw some of their money at perception and make their product 'objectively better', then Microsoft can just fire their cash cannons back and we're off to the races. This is the essence of wikilobbying." - Stephen Colbert

-

|

Comprehending Across a Dozen Information Literacies

If schools must equip the young with the skills to understand their world, then they will prepare them for delving into different categories of information - each of which represents an essential literacy:

- Text

- Numerical

- Visual

- Media

- Ethical

- Social

- Cultural

- Environmental

- Natural

- Emotional

- Artistic

- Kinesthetic

When meanings are not directly stated and must be inferred, the comprehension challenge is dramatically exacerbated. Students who are accustomed to finding explicitly stated meaning may not know how to manage when significance is implicit and obscured or simply unavailable. Latent truths require digging and synthesis rather than simple scooping. They actually may not even exist until pieced together by the thinker.

While schools may not have devoted much attention to synthesis in the past, it has become the crux of our challenge as educators in this century. We have reached a stage that requires the construction or making of meaning from clues, data and bits of evidence that will only make sense when we have learned to handle them like the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. While schools may not have devoted much attention to synthesis in the past, it has become the crux of our challenge as educators in this century. We have reached a stage that requires the construction or making of meaning from clues, data and bits of evidence that will only make sense when we have learned to handle them like the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle.

That puzzling depends on a potent mix of wondering, pondering, wandering and considering. The simple convergent thinking of previous decades does not suffice, especially when the questions or issues at hand are more mysterious than puzzling.

Puzzles often have right answers and their pieces may actually fit together nicely, while the mysteries may prove more elusive.

|

Googling for the Truth

Both young and old come to trust Google or Wikipedia to provide them with the truths they need, whether it be the lyrics to a song, the best treatment for prostate cancer or an inexpensive hotel in Shanghai.

Often the results of such searches prove useful and even illuminating, but the limitations of this prospecting may not be evident to all. Some who turn to Wikipedia do so without realizing that the authors of articles may be very biased or poorly informed.

Google offers an intriguing search option. When you arrive at the basic Google page, you will see the option "I'm feeling lucky" below the search box. Select this option, type in the word "truth" and see what happens.

Google usually takes you to http://thetruth.com. Wouldn't it be nice if finding the truth were so simple?

What do they mean by "I'm feeling lucky?"

They invite us to surrender to their judgment as to which Web site best serves the question asked. "I'm feeling lazy," is a more accurate wording for such surrender. How reliable is their judgment? Judge for yourself. (Go to article, "Feeling Lucky? Surrendering to Pundits, Wizards and Mindbots."

|

Wondering, Pondering, Wandering and Considering

For the young to make their own meanings, they need to be able to shift back and forth across the four operations of wondering, pondering, wandering and considering. Each has its own role and its own time, but sometimes they may operate concurrently.

Under the old topical approach to school research, students were asked to do little more than scoop and smush. It was all about finding information rather than building an answer or solving a mystery. Little comprehension was involved. Under this approach a student might learn when George Washington was born and what battles he fought, but it was rare that schools might ask questions of import like those below requiring some real wondering, pondering, wandering and considering:

- In what ways was the life remarkable?

- In what ways was the life despicable?

- In what ways was the life admirable?

- What human qualities were most influential in shaping the way this person lived and influenced his or her times?

- Which quality or trait proved most troubling and difficult?

- Which quality or trait was most beneficial?

- Did this person make any major mistakes or bad decisions? If so, what were they and how would you have chosen and acted differently if you were in their shoes?

- What are the two or three most important lessons you or any other young person might learn from the way this person lived?

- Some people say you can judge the quality of a person's life by the enemies they make. Do you think this is true of your person's life? Explain why or why not.

- An older person or mentor is often very important in shaping the lives of gifted people by providing guidance and encouragement. To what extent was this true of your person? Explain.

- Many people act out of a "code" or a set of beliefs which dictate choices. It may be religion or politics or a personal philosophy. To what extent did your person act by a code or act independently of any set of beliefs? Were there times when the code was challenged and impossible to follow?

- What do you think it means to be a hero? Was your person a "hero?" Why? Why not? How is a hero different from a celebrity?

Such questions of import quoted from the Biography Maker cannot be answered with simple scooping and smushing. They are in line with the demanding comprehension questions asked by the NAEP reading test.

Wandering and Stumbling to Meaning

When students have experienced only the scooping and smushing model, they have little grasp of what it means to explore a question of import. Basic to this kind of research is the realization that because they do not know what they do not know, they must be careful not to organize their research around what little they do know, as the limits of their understanding may block them from uncovering much that is novel or surprising.

Questions of import, being puzzles or mysteries, almost always require that the researcher muck around a bit, digging into the raw information like a detective seeking clues.

When it comes to biographies, students are usually accustomed to reading secondary sources and have little awareness of how to delve into correspondence, diaries, news accounts or other sources that might cast light on the person's character and provide the kind of evidence that could support them in forming their own opinions. Relying upon secondary sources is especially dangerous with historical figures like Thomas Jefferson or Captain James Cook because many of them have been turned into icons and heroes. The biographies may have "Photoshopped" the hero, leaving out unflattering stories, atrocities and major character flaws. For an example of Photoshopping, take a look at this Dove video called "Evolution" at YouTube. For an article about Photoshopping reality go to "Photoshopping Reality: Journalistic Ethics in an Age of Virtual Truth."

A vivid example of such badly written and unsubstantiated material can be found, sadly, on the Web site of the Canadian National Library:

- Many believe that James Cook was the greatest ocean explorer ever to have lived, and that he mapped more of the world than any other person. It cannot be denied that he combined great qualities of seamanship, leadership and navigational skill.

- Source

The diaries and letters of historical figures can sometimes provide a very different view of them than what we might find in an encyclopedia or other secondary sources, but sometimes encyclopedias do a surprisingly good job, as is the case with "Thomas Jefferson - American in Paris" an Encyclopædia Britannica article at http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-61878/Thomas-Jefferson

- But the Paris years were important to Jefferson for personal reasons and are important to biographers and historians for the new light they shed on his famously elusive personality. The dominant pattern would seem to be the capacity to live comfortably with contradiction. For example, he immersed himself wholeheartedly in the art, architecture, wine, and food of Parisian society but warned all prospective American tourists to remain in America so as to avoid the avarice, luxury, and sheer sinfulness of European fleshpots.

We must teach the young to wander back and forth between secondary and primary sources, learning from the opinions of others while testing them against the evidence.

After reading the EB article, for example, we might read Thomas Jefferson's love letters to Maria Cosway. No matter how carefully we review the evidence, however, his romantic relationships will probably always remain a mystery, whether it be with Maria or his relationship with a household slave, Sally Hennings, who may have given birth to several of his children.

In contrast to Jefferson, George Washington's daily journal entries tell us almost nothing about his thoughts and very little detail about his activities. Famous people vary greatly in terms of the tracks they leave behind and primary sources can prove as misleading and distorted as secondary sources.

It takes some wandering about to learn about these people. If the student finds GW's diaries disappointing, she or he must wonder where else to look. Wondering leads to renewed wandering that in turn inspires considering and pondering, all of these in service to the goal of understanding or comprehending the character of the figure being investigated.

Introducing Wandering as a Research Approach

Because many students will arrive in class with nothing much more than the scoop and smush model, teachers must acquaint them with the wandering model mentioned above by conducting what amount to information "field trips" - taking them on productive wanderings that lead to insight, discoveries and an occasional "Aha!" Knowing that this type of learning may be entirely new to students, teachers must provide what amounts to a field guide to wandering about1. That field guide must be adapted to match the kinds of data available for various disciplines, with social studies and science each having their own types of information landscapes and challenges, but one good example of such resources might be "Using Primary Sources in the Classroom" available at the American Memory section of the Library of Congress.

1. This notion of purposeful wandering occurred to me before reading A Field Guide to Getting Lost by Rebecca Solnit, but her book is a wonderful extension of the concept and a delightful read.

|

|

While schools may not have devoted much attention to synthesis in the past, it has become the crux of our challenge as educators in this century. We have reached a stage that requires the construction or making of meaning from clues, data and bits of evidence that will only make sense when we have learned to handle them like the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle.

While schools may not have devoted much attention to synthesis in the past, it has become the crux of our challenge as educators in this century. We have reached a stage that requires the construction or making of meaning from clues, data and bits of evidence that will only make sense when we have learned to handle them like the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle.