|

| Vol8|No2|December|2011 |

|

Please feel free to e-mail this article to a friend, a principal, a parent, a colleague, a teacher librarian, a college professor, a poet, a magician, a vendor, an artist, a juggler, a student, a news reporter or anyone you think might enjoy it. Other transmissions and duplications not permitted. (See copyright statement below).

A Truly Open Mind

By Jamie McKenzie

About Author © 2011, all rights reserved

-

|

|

This is Chapter 4 from Lost and Found, Jamie's new book.

The world is full of people who have never, since childhood,

met an open doorway with an open mind.

E.B. White

Who would argue against approaching life’s thorny questions and issues with an open mind? It seems obvious at the outset that one will not get very far with a closed mind; yet a truly open mind is a bit like a four leaf clover—rare and elusive.

Sadly, current cultural norms tend to insulate and isolate all of us from contrary opinions, evidence and experience. Much of what we see and learn has been filtered before it is allowed consideration. We often rely upon remnants—fragments that have slipped through the netting of our preconceptions and preferences.

Christine Rosen calls this phenomenon egocasting:

By giving us the illusion of perfect control, these technologies risk making us incapable of ever being surprised. They encourage not the cultivation of taste,

but the numbing repetition of fetish. And they contribute to what might be called “egocasting,” the thoroughly personalized and extremely narrow pursuit of one’s personal taste.

“The Age of Egocasting” The New Atlantis, Fall 2004/Winter 2005

Egocasting and closed-mindedness are closely associated. Operating with an open mind requires penetrating levels of self knowledge to clear away the netting and the filters mentioned above. It is the mental equivalent of stripping varnish and stain from an old chest of drawers—but far more challenging, since much of the webbing is invisible. We may be living in a cocoon of our own making. Though we may be sheltered and isolated, the threads of our cocoon will usually be imperceptible. Many of us are living blind to important aspects of reality in the sense of the song Amazing Grace, but we probably believe that we are sighted and quite well informed.

I remember the “Aha!” I felt when I read Rosen’s essay and recognized my own cocoon. It was an important awakening and the start of a personal “un-threading” as I tried to identify the ways that I had isolated myself and narrowed my thinking.

There is a tendency for most of us to seek mental equilibrium—a balance akin to what Melville would call “staying ashore.” How much uncertainty and turbulence can any of us manage? But the price of balance may be the blindness mentioned earlier. “Don’t trouble me with the facts—especially the disturbing facts!”

When information creates cognitive dissonance, true learning may begin, but dissonance is a bit like Melville’s heavy seas. The turbulence of real thought and discovery can be unnerving.

Most college students are asked to consider the cave allegory offered up by Plato in The Republic, but it is unlikely that this allegory will make much impact on us when we are 19 or 20 years old. The allegory is meant to warn us against the cocoon, but the warning probably comes a bit early in life. Just as the saying “You have to suffer to sing the blues!” rings true, there is probably something similar that might capture the concept of mental ripening.

It may be difficult to recognize the threads of your cocoon before it is woven. Ironically, it may be even more difficult after it is woven. The question becomes, at what age does the cocoon start? and to what extent are we born into a cocoon because of our social position and the cultural influences we have been born into?

Conventional definitions of open-mindedness are somewhat limited—emphasizing receptivity—a willingness to listen or consider. This view does not adequately address the issue of the cocoon. Open-mindedness in a modern context requires an active stance—a conscious effort to step past the filtering that blocks most disturbing information before it can arrive. Open-mindedness must include exposure to streams of data and information that might shake core beliefs at their foundation. The Grimke sisters mentioned in the previous chapter provide a dramatic example of open-mindedness as their revulsion at the cruelty they witnessed in their own home set them on a spiritual journey that took decades.

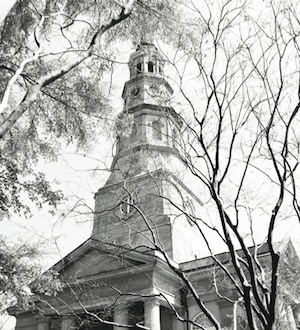

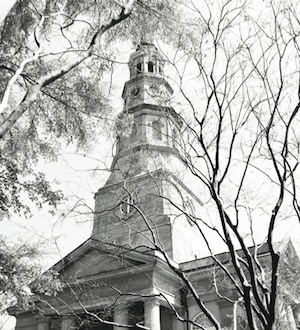

Seeking a new church

Growing up in a Charleston slave-holding family, the Grimke sisters each grew increasingly uncomfortable with the disconnect they saw between the preaching of their family’s church (Saint Phillip’s Episcopal Church) and their own reading of the Bible. Growing up in a Charleston slave-holding family, the Grimke sisters each grew increasingly uncomfortable with the disconnect they saw between the preaching of their family’s church (Saint Phillip’s Episcopal Church) and their own reading of the Bible.

Deeply religious, they could not reconcile the church’s upholding the institution of slavery with their own understanding of Jesus and his message. Each of them had witnessed cruelty that seemed unchristian to them.

The resulting cognitive and spiritual dissonance set the two sisters on a lifetime search for a church that would honor the values of Jesus not only in the words spoken but the actions taken. Their search for a church over several decades is

a dramatic example of the kind of purposeful wandering advocated

by this book, since they both ended up leaving the pro-slavery cocoon of their home town for Philadelphia where they explored the possibilities of Quakerism; yet, even though they found much to admire in their new religion, they remained uncomfortable with the Friends’ reluctance to take a strong stand for the abolition of slavery.

The story of their search and their spiritual wandering is told in detail by Mark Perry in Lift Up Thy Voice. As they learn to question the attitudes and the behaviors of the various churches they attend, they also seek mentors and like-minded individuals who encourage them in their search for a decent society. After many years, it becomes apparent to them that the society itself must change—that slavery must be abolished and equal rights established. Rather than accept the cocoon into which they were born, both sisters became champions of change—open-minded in a radical sense.

My own wandering about Charleston in April of 2010 led me

to the plantation that first made me aware of the Grimke family, but during this same visit, I had enjoyed an afternoon of photography in a city that is marked by many church spires. I had no idea when I took the picture of Saint Phillip’s Episcopal Church on this page that it would end up in this book. At that time I knew nothing of the Grimke sisters, their church or their relevance to this book. I stumbled onto their story after I returned from Charleston, and it was only in reading Lift Up Thy Voice that I drew the connections.

The clown and the critic

Back in 1993, I wrote the following paragraphs about open- mindedness for Administrators at Risk: Tools and Technologies for Securing Your Future. They are worth repeating in this chapter.

What is an open mind?

A mind that welcomes new ideas. A mind that invites new ideas in for a visit. A mind that introduces new ideas to the company that has already arrived. A mind that is most comfortable in mixed company. A mind that prizes silence and reflection. A mind that recognizes that later is often better than sooner. An open mind is somewhat like silly putty. Do you remember that wonderful ball of clay-like substance that you could bounce, roll and apply to comics as a child?

An open mind is playful and willing to be silly because the best ideas often hide deep within our minds away from our watchful, judgmental selves. Although our personalities contain the conflicting voices of both a clown and a critic, the critic usually prevails in our culture. The critic’s voice keeps warning us not to appear foolish in front of our peers, not to offer up any outrageous ideas, and yet that is precisely how we end up with the most inventive and imaginative solutions to problems. We need to learn how to lock up the critic at times so the

clown can play without restraint. We must prevent our internal critic from blocking our own thinking or attacking the ideas of others.

An open mind can bounce around in what might often seem like a haphazard fashion. When building something new, we must be willing to entertain unusual combinations and connections. The human mind, at its best, is especially powerful in jumping intuitively to discover unusual relationships and possibilities. An open mind quickly picks up the good ideas of other people, much like silly putty copying the image from a page of colored comics. The open mind is always hungry, looking for some new thoughts to add to its collection. The open mind knows that its own thinking

is almost always incomplete. An open mind takes pride in learning from others. It would rather listen than speak. It loves to ask questions like, “How did you come up with that idea? Can you tell me more about your thinking? How did you know that? What are your premises? What evidence did you find?”

The open mind has “in-sight”—evaluating the quality of its own thinking to see gaps that might be filled. The open mind trains the clown and the critic to cooperate so that judgment and critique alternate with playful idea generation.

The pain of non-conformity

Sometimes the price of an open mind may be alienation from one’s own group, family and times. The Grimke sisters certainly found this to be true as their leaving the local church and then Charleston were viewed as terrible embarrassments to their family. When they returned for visits wearing simple Quaker garb, they were ridiculed. But those who pushed the abolitionist cause were subject to far more violent and dangerous harassment, as it was not unusual for their meetings to be broken up by angry mobs in Northern cities. If an

open mind leads one to challenge conventional thinking, the order

of the day, or what passes for patriotism at a given time in history, >

the consequences can be quite painful. At the same time, to deny

these differences can lead to a different kind of pain, as Henry Miller suggests:

Everything we shut our eyes to, everything we run away from, everything we deny, denigrate or despise, serves to defeat us in the end. What seems nasty, painful, evil, can become a source of beauty, joy, and strength, if faced with an open mind.

Henry Miller

This quotation reminded me of Arthur Miller’s work, The Crucible, a play that explores the pressures and moral dilemmas experienced by the good people of Salem when many citizens were accused of witchcraft and their neighbors began to question the feeding frenzy that led to nineteen hangings and quite a few more deaths. As Miller’s play makes evident, it was dangerous to challenge the wisdom of the crowd, the justice of the judges, or the Christianity of the ministers. First performed in 1953, Miller’s play was an allegorical reference to the McCarthy hearings of that time—witch trials of a different flavor.

In 2010, mass hysteria and fear of Islam in the U.S.A. led to

local protests against the building of new mosques, as the New York Times reported on June 10, “Opposition to new mosques has become almost commonplace” in the article “Heated Opposition to a Proposed Mosque.”

In a nation established, in part, to protect the freedom of religion, some citizens are quick to limit the extension of such rights to those of other religions—drawing a connection between terrorism and Islam that is extremely tenuous.

During any phase of history, nations, cultures, political parties and churches may demand loyalty to certain beliefs and may squash or silence those who think independently. It takes great courage to persist with your own politics or poetry under such conditions as did Osip Mandelstam, the Russian poet, who died in a concentration camp during Stalin’s regime.

Boris Pasternak, another Russian poet, narrowly escaped a similar fate and was pressured to turn down the Nobel Prize for his controversial novel, Dr. Zhivago. In what seemed like a warning

to Pasternak, his lover was twice sent to the camps for five-year sentences and interrogated at length regarding Pasternak’s beliefs.

For many others, closed-mindedness is simply a matter of faith. One knows what one knows, believes what one believes and wishes to devote little or no time to review or revision. For such people, life is

a matter of givens—beliefs you can count on to get you through life. There may be a book outlining this way of thinking. The individual counts on these ideas as articles of faith. They are unquestionable, given, absolute and reliable. Challenging these beliefs would seem wrong-minded, ill-advised and even heretical. The true believer wastes little time testing these ideas and may view those who do challenge the ideas as dangerous. As John Dewey warned:

The path of least resistance and least trouble is a mental rut already made. It requires troublesome work to undertake the alternation of old beliefs. Self-conceit often regards it as a sign of weakness to admit that a belief to which we have once committed ourselves is wrong. We get so identified with an idea that it is literally a “pet” notion and we rise to its defense and stop our eyes and ears to anything different.

John Dewey

When a culture, a nation, or an organization prizes independent thinking and open-mindedness, the life of the average citizen or employee is quite different from that of those working or living where conformity is prized. Pink Floyd’s rock opera, The Wall, portrays the consequences of oppressive conformity in vivid, very disturbing terms as Pink, the main character, finds his poetry mocked and ridiculed at school. In many scenes reminiscent of Nazi Germany, we see individuality, creativity and imagination squashed.

And I have become comfortably numb.

Pink Floyd

|

|

.

Copyright Policy: Materials published in The Question Mark may be duplicated in hard copy format if unchanged in format and content for educational, nonprofit school district and university use only and may also be sent from person to person by email. This copyright statement must be included. All other uses, transmissions and duplications are prohibited unless permission is granted expressly. Showing these pages remotely through frames is not permitted.

FNO Press is applying for formal copyright registration for articles.

Unauthorized abridgements are illegal.

|

|

|

Growing up in a Charleston slave-holding family, the Grimke sisters each grew increasingly uncomfortable with the disconnect they saw between the preaching of their family’s church (Saint Phillip’s Episcopal Church) and their own reading of the Bible.

Growing up in a Charleston slave-holding family, the Grimke sisters each grew increasingly uncomfortable with the disconnect they saw between the preaching of their family’s church (Saint Phillip’s Episcopal Church) and their own reading of the Bible.