|

Because of my extensive travels during the past decade to cities in China, Australia, New Zealand, the USA and Canada, my running has taken me into neighborhoods rarely visited by tourists. Many mornings I set off with no map and no real plan other than the intention to cover 12-18 miles without getting completely lost or mugged.

Almost all of these long runs are some kind of “out and back” experience, as I have learned that loops are sometimes self-defeating. Despite my best intentions and skills, whenever I attempt a loop without some kind of map, I tend to get lost. For this reason, many of these runs are a matter of running out for a distance and then retracing my steps. Dozens of runs have taught me that many of the most interesting (to me) aspects of a city do not appear on the list usually handed to tourists. Since most visitors have few days to explore, they are often provided with a short list of iconic sites. Because I am looking for experiences that are less iconic and possibly more authentic, I have worked on strategies to help me find the restaurant loved by locals but unknown to tourists. I seek the neighborhood that may be “down home” and infused with antique charm. This neighborhood is unlikely to appear on the “must do” list presented to tourists.

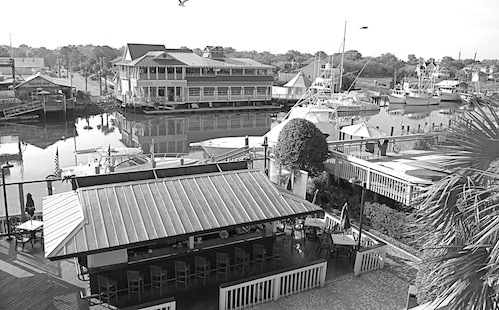

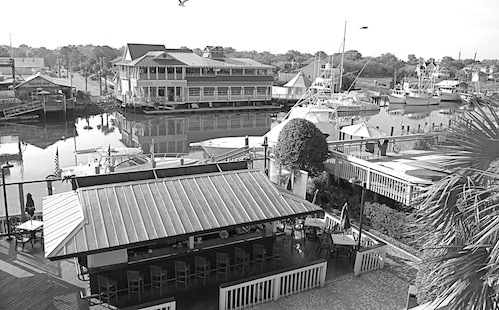

In this case, I discovered the town of Mt. Pleasant a year earlier by making a wrong turn and crossing a magical bridge. The bridge deserved a run of its own, spanning Charleston harbor in a dramatic fashion and promising great views. After the run, I drove around and found Shem Creek and a half dozen shrimp shacks and seafood restaurants. Returning the next day to sample the shrimp, I noticed an inn across the creek that seemed promising, and a year later I found myself vacationing in the Shem Creek Inn at half the cost of pricey downtown Charleston with a delightful room overlooking the creek as well as an active bar scene that would make Jimmy Buffett happy.

Having run the bridge once again on the first day of this holiday, I was curious to discover what lay on the other side of the creek I could see from my hotel room pictured on the previous page. This curiosity led me to Google Map. I started in map view and soon found a street that seemed to reach out into the harbor and then stop without any reason.

I was immediately curious to see why this street came to such an abrupt stop. In the map below, you can see Pitt Street at the bottom. This is what prompted me to shift from Map View to Satellite View, wondering what that point might offer.

The Satellite View showed so much more than roads. The online view is in color. You could see that the road was changing into something else — something that might be worthy of a run. There was the hint of magic and mystery.

And this mystery encouraged me to zoom in further. Eventually, of course, the satellites and Google reached their limits and I realized that I must run to the bridge to explore first hand.

What does this have to do with schools and learning?

As mentioned earlier, this discussion of Pitt Street is meant as a metaphor for the spirit and the strategies involved in exploring unknown territory — getting off the beaten path, testing uncharted areas of knowledge or spatial areas like this section of Mount Pleasant.

The learner probes, digs and surveys. Walking (figuratively) near the swamp, she or he has eyes open for the alligator or new idea lurking and well camouflaged — the insight or discovery rarely noticed by the casual passerby.

It is not just a matter of having an open mind and a willingness to step off the beaten path. There is a way of searching with one’s mind — a piercing kind of seeing and grasping that converts experience into insight.

In some respects, it is easier to learn how to wander purposefully over physical space than it is to do the same with information and ideas. At the same time, once one grasps the physical metaphor, that understanding can support the mental equivalent. In some respects, it is easier to learn how to wander purposefully over physical space than it is to do the same with information and ideas. At the same time, once one grasps the physical metaphor, that understanding can support the mental equivalent.

In working with students, the physical adventuring becomes a great way to introduce and then develop the habits of mind and thinking skills proposed in this book.

Getting Past Conventional Wisdom Getting Past Conventional Wisdom

Another way of thinking about the theme of this chapter is to consider the tendency of much of the world to rely upon what is called “conventional wisdom” when researching most topics or questions. Although it makes sense to consider conventional wisdom while formulating one’s own position, reliance upon such ideas, opinions and theories can be both limiting and dangerous.

The online Merriam-Webster defines CW as “the generally accepted belief, opinion, judgment, or prediction about a particular matter.” Despite recent books extolling the wisdom of the crowd, history reminds us that the crowd, the mob and the masses are often wrong about things — often biased or easily swayed by propaganda and appeals to emotion by unscrupulous demagogues.

Unfortunately, CW often turns out to be mistaken — as in the field of medicine and health. The CW of one decade about swimming after eating is replaced by the CW of the next decade, and so on and so on. Many proponents of a particular cancer treatment rely upon the power of CW to help sell their speciality, claiming, for example, that surgery is the “gold standard.” The implication is that any other treatment is substandard, cheap and unlikely to produce good results.

Take it on faith!

Think of conventional wisdom as the beaten path explored in this chapter. When we learn to think for ourselves and make up our own minds, we weigh CW in the balance, but we do not rely upon it.

An Example from History

Visiting plantations in the current century raises some intriguing issues of fact and judgment, as information about plantation conditions and the behavior of owners is murky. Few slaveholders kept records of whippings and punishments that have survived until today. It is hard to find documents showing how many slaves died each year on a particular plantation from malnourishment or illness brought on by working long days in the swamps to grow rice. Before we grant any one owner the benefit of the doubt and conclude that they were kind to their slaves, treated them well in housing, food, medical treatment and punishment, such evidence would be helpful.

In the years before the Civil War proponents of slavery argued that the Bible sanctified slavery. They also claimed that most slave owners were kind in their treatment. Even after slavery’s end, there was a tendency to downplay the hardship, the cruelty and the dangers associated with the slave years. Novels like Gone with the Wind painted a charming picture of life on the plantation and turned the slave owners and their families into sympathetic characters. Most paintings of life on planations romanticized them and paid little attention to the actual conditions experienced by slaves.

Some of these perceptions remain today and the issue of celebrating Confederate history is in the headlines as several governors have proposed formal celebrations. In the case of Virginia, the Governor made no mention of slavery in his proposal, as if we can all pretend it never happened and the Civil War was really all about other matters such as the North’s wish to dominate the South financially.

Visiting the Magnolia Planation, it is difficult to figure out what type of person owned the plantation before and after the Civil War. The Plantation does a good job of providing a few clues that are telling, but judging the character of the Rev. John Drayton Grimke is like coming up with a 1,000 piece jigsaw picture when you only possess a half dozen pieces.

Walking through the gardens you come upon one sign that explains how raising rice in the swamps was terribly difficult work for the slaves. Since the Reverend owned 300 slaves that did this work and supported his gardening, we can read between the lines but still want to know how many of these slaves were whipped and how many died from malaria and other diseases typical of such rice plantations.

PBS is quite clear about the risks and hardships experienced by slaves on such plantations, but there is no hard data available to figure out what happened on the Magnolia Plantation.

- The rice plantations were the most deadly. Black people had to stand in water for hours at a time in the sweltering sun. Malaria was rampant. Child mortality was extremely high on these plantations, generally around 66% — on one rice plantation it was as high as 90%. Source: PBS People & Events Conditions of antebellum slavery 1830 - 1860 http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part4/4p2956.html

The victims of slavery on such a plantation generally did not possess the skills or the opportunities to document what happened to them unless they escaped to the North and reported their experiences to white and black abolitionists who might write down their stories and use them in the battle to end slavery.

Because we have few facts to go on, some clues may take on unwarranted weight.

We learn, for example, on a sign near one tree where the Reverend liked to sit and meditate most days, that he was such a firm Christian that he refused to attend his own daughter’s marriage to a young man because that young man had expressed some religious doubts. This clue does not make us warm to the Reverend unless we share his sanctimonious certainty. We wonder if he was moralizing, preachy, smug, superior and priggish?

But then we learn that his chief overseer and plantation manager, a slave by the name of Adam Bennett, was strung up by Sherman’s troops who tried to pry from him the secret hiding place of Grimke family treasures. He refused to cooperate, survived and eventually made a 250 mile journey to meet his former master and return to the plantation. In the following years, he regained his management role as the Reverend sold some land to get enough funds to continue his gardening.

This story is often mentioned in various magazine and newspaper articles as evidence that the Reverend was one of the kind masters.

While the story shows a high degree of loyalty, it also leaves many questions unanswered, since the overseer of many plantations might also be the enforcer — the man who administered the whippings and discharged the discipline of the plantation. In some cases he was white. In others he was black. Loyalty to a former master by an overseer could mean many different things.

The same could be said about the inference that the Reverend was a kind master because he (illegally) taught slaves the 3Rs under the subterfuge of religion. Religion and the Bible were used by slave owners to justify slavery and to help slaves (and women) understand their subservience. It is naive to think kindly of those who offered religious training to their slaves, especially when the brand of religion was so strict that the Reverend refused to attend his own daughter’s wedding.

Such kind thoughts persist readily in the absence of evidence to the contrary. For the purposes of this chapter, the notion that the Reverend was a “kind master” serves as an example of the “beaten path.” The claim has been made repeatedly over the years so that it is difficult to find anyone or anything challenging that belief.

Following the research strategies advanced in this chapter and this book, I was able to find puzzle pieces that increased my doubt about the Reverend but did not approach certainty. The issue will probably remain clouded in mystery no matter how far afield we search. What we really need are plantation records of whippings, deaths and rations.

In wrestling with this mystery, I stumbled into a disturbing story of a Grimke relative living on the land next to the Reverend who settled down with one of his slaves when his wife died — an octaroon by the name of Nancy Weston. He had three sons by this slave mistess that he willed to his son. When he died suddenly of tubercolosis, she and her sons moved to a house in Charleston, and later two of the boys were pressed into household service by their half brother (and owner) Montague Grimke. According to several acounts, he subjected his half brothers to harsh treatment:

- Henry died in 1852, just before John, his third son was born, named by Nancy Weston after Henry’s brother, Thomas Grimke, my great-great-great grandfather. Montague allowed Nancy and her sons to live in a small house on Coming Street in Charleston, but little else. It appeared that despite the stipulation that they be well-treated as family, their lives were spent in great poverty with Nancy trying to make ends meet as a seamstress and washerwoman.

Five years after Henry’s death, Montague took her two eldest sons as house servants, and they were regularly beaten and as a consequence tried on many occasions to escape. They also experienced the cruelty of the “Sugar House”, where harsh punishments were meted out. Montague had in fact reneged on his own father’s will, and not recognized the boys as his half-brothers.

Excerpt from Let My People Go Free By Bill Grimke-Drayton

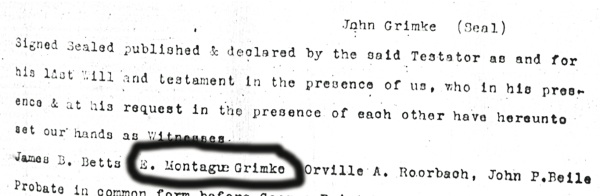

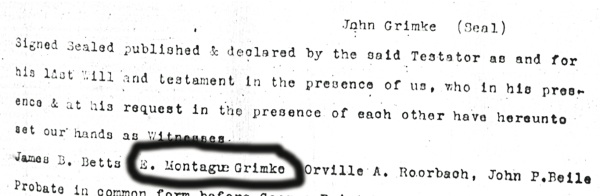

How well did the good Reverend owner of the Magnolia Plantation know this relative Montague who had his own half brothers beaten? In wandering about through the historical records, I found Montague’s will, dated and signed by the good Reverend as a witness.

While bearing witness to a will is not the same as approving of the man’s behavior toward his half brothers, it substantiates the close connections held by these slave owners and weakens the case that the good Reverend was “one of the good ones.” As the beatings, the breaking up of families and the deaths from working in the swamps fade into the fog of history, safely hidden from view by a lack of record- keeping, myths are free to surface and truth becomes elusive.

As a learning process, the search for evidence about the good Reverend took me to unexpected places and opened my eyes to aspects of U.S. history that were new to me. As I read about Montague’s mistreatment of his half brothers, I found that two of his cousins — Sarah and Angelina Grimke — were so upset with the institution of slavery that they left Charleston for good, moved to Philadelphia, became Quakers and ended up being major figures in the movement to abolish slavery.

The diaries of Sarah Grimke make it quite clear that whippings of slaves took place on a frequent basis within their household and suggest that it was typical for most families holding slaves. Her revulsion at the cruelties of slavery was accompanied by a questioning of any religion that might endorse such inhumanity.

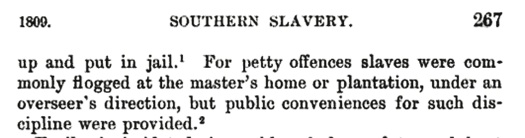

The harsh treatment of slaves throughout slave-holding families is well documented but somehow conveniently forgotten — whitewashed, if you will. Writing in 1894, History of the United States of America, under the constitution [1783-1865], James Schouler comments about floggings in Charleston:

In his footnote, he comments, “Lambert and Davis, the travellers, both of whom saw much of South Carolina life at this period, make mention of the Charleston jail, or sugar-house, where lashes were laid on at a shilling a dozen.” It was this “Sugar House” where Montague Grimke sent his half brother-slave for a whipping. Other commentators have described the horrors of the Sugar House at some length.

In his Roving Editor published in 1859, journalist James Redpath makes the following comments:

- If any slaveholder, from any or from no cause, desires to punish his human property, but is too sensitive, or what is far more probable, too lazy to inflict the chastisement himself — he takes it (the man. woman or child), to the Sugar Hoise, and simply orders how he desires it to be punished . . .

Page 60

At the time he published his book, his interviews of slaves and his comments about slavery were dismissed as abolitionist fabrications by those who upheld the institution of slavery, but John R. McKivigan, an Associate Professor of History at West Virginia University has traced his travels and found documents to substantiate his travels.

While one part of the Grimke family was treated as slaves by some of its white members, not all white Grimke family members drew that color line. After the Civil War, the Grimke sisters became aware of their half black cousins, contacted them and helped two of them to attain university degrees.

The story of Sarah and Angelina Grimke is well told in Lift Up Thy Voice, a Grimke family history written by Mark Perry. The cover of his book shows the slave mother, Nancy Weston, with her three sons (grown) posing in dark suits in the background. It is worth noting that this book is about all of these Grimkes related by blood and slavery — Sarah, Angelina, Montague and the three sons of Nancy Weston and Henry Grimke — Archibald, Francis and John.

The subtitle of Perry’s book is The Grimke Family’s Journey from Slaveholders to Civil Rights Leaders, but it should read The Grimke Family’s Journey from Slaveholders and Slaves to Civil Rights Leaders. Archibald graduated from Harvard Law School and went on to

be one of the founders of the NAACP. Francis became a minister and important leader in Philadelphia.

What began as skepticism during a visit to a showplace plantation took me off the beaten path into pages of history darkened by pain, betrayal and exploitation — the use of the Bible to justify human behavior at its worst — but the story also came to illuminate people at their best as the Grimke sisters repudiated this system, fought for Abolition and forged friendships with two of their half cousins, each of whom went on to play important leadership roles in the battle for equal rights.

|

In some respects, it is easier to learn how to wander purposefully over physical space than it is to do the same with information and ideas. At the same time, once one grasps the physical metaphor, that understanding can support the mental equivalent.

In some respects, it is easier to learn how to wander purposefully over physical space than it is to do the same with information and ideas. At the same time, once one grasps the physical metaphor, that understanding can support the mental equivalent. Getting Past Conventional Wisdom

Getting Past Conventional Wisdom